Universal Horror Classics: Comfort Food for the Senses (Part Two)

PART TWO: THE SECOND GOLDEN AGE

Starting in 1936, there was a slump in horror’s popularity, no doubt because it was being eclipsed by the real-life horrors taking place in Nazi Germany. Not only did it cost Universal a lucrative market — it cost Uncle Carl Laemmle his job as well. The new owners decided to try to emulate MGM with lush musicals. Even Bride of Frankenstein director James Whale made a successful version of Show Boat.

Singer Deanna Durbin kept the studio afloat from 1937 to the end of the decade, while the monsters waited in the wings, anxiously tapping their claws.

Theaters began running double features of the original Dracula and Frankenstein in 1938, whetting the appetites of horror hounds and making lots of cash. Universal, always angling to exploit an asset, brought out its A-team — Karloff and Lugosi — to star in Rowland V. Lee’s 1939 Son of Frankenstein. Unhappy to be cast again as the monster, Boris was given little more to do than grunt and murder. But Lugosi had the opportunity to portray a really grotesque character and steal the show in the process. His vengeful Ygor, neck and spine twisted as the result of an unsuccessful hanging, resurrects the creature to exact his revenge on the jurors who falsely found him guilty of body-snatching (hence the hanging).

Son is, of course, the film upon which Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein was based. Basil Rathbone plays the titular son, driven by the perverse Ygor to get the monster back into fighting shape. Ygor even donates his own brain to give it human intellect.

Universal was considering making the film in color (this was 1939, after all — the year of Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind) but Karloff’s makeup was deemed too cartoony.

More sequels followed, but Boris, who suffered permanent, debilitating back pain as a result of the heavy suits the monster was required to wear, declined to don the stitches and bolts. His career in Universal horror was certainly not over, however.

Creighton Chaney, son of Universal’s silent superstar Lon Chaney, rechristened himself Lon Chaney Jr. and started a film career of his own. He spent years in the periphery of Hollywood, playing secondary roles in cowboy movies, serials and studio comedies. His big break came when he played Lennie in Lewis Milestone’s 1939 Of Mice and Men, and he arrived at Universal ready to take up the Chaney mantle some ten years after his father’s passing.

The studio was delighted to cast the son of “the man of a thousand faces” as The Wolf Man in 1941, and the result was solid gold. This film is also where Universal’s uniquely mittel-European vision began. It’s a strange, time warpy place. The leads are clad in contemporary (for the time) 1940s garb while secondary and background players are dressed in various unrelated period costumes.

For example, look at the photo seen here of Chaney as the cursed Larry Talbot with gypsy woman Maleva. He’s all snazzed up in suit and tie, while she and her wagon seem to have just arrived from another era. 1700s? 1800s? Who knows?

As the tortured Talbot, Lon gives a nice performance, but Claude Rains, the Invisible Man himself, playing the father who is forced to kill the monster his son has become, is truly the emotional center of the film.

Another major cult figure emerged here — the aforementioned gypsy, Maria Ouspenskaya. She was a Russian actress and teacher who fit into the mix-and-match Universal milieu just perfectly. Her recitation of “Only a man who is pure of heart and says his prayers by night…” is legendary.

As Universal’s new horror star, Chaney was granted a film series (Inner Sanctum) and assigned the unlikely role of Count Alucard (hint: it’s spelled backwards!) in Son of Dracula in 1943. Chaney was too large and lumbering to effectively portray the (literal) lady-killer, so it all was rather comical. However, this was the first film to showcase special effect artist John P. Fulton’s nifty bat-to-man transformation, so there was that.

Also in 1943, Frankenstein met the wolf man, which started everyone on the bad habit of referring to the monster as “Frankenstein,” which is not correct. Chaney returned as Larry Talbot, and Lugosi, who refused to play the creature in 1931, stepped into Karloff’s shoes for this one. It was weird — Lugosi just looked like Lugosi in Frankenstein monster drag!

Musicals were big in the ’40s, so the studio’s new owners decided that all their films should have some sort of musical entertainment, regardless of how it fit in. Here, the villagers gather together for an impromptu number, Faro La Faro Li, in celebration of the new wine. It’s quite hilarious.

That same year, the studio remade Phantom of the Opera, this time in color and featuring (now) creaky opera stars Nelson Eddy and Susanna Foster. The studio’s opportunistic new musical direction ruined it. The original Phantom Stage 28 was reused and Claude Rains played Erik, but all he did was wander around the opera house while the two leads trilled away endlessly. What a bore.

But encouraged by the box office results for Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, Universal decided that if two monsters were good, three were better, and the “monster rally” was born. 1945’s House of Frankenstein brought together the monster (Glenn Strange), the wolf man (Chaney) and Dracula (John Carradine), with Boris Karloff playing the mad scientist for good measure.

But encouraged by the box office results for Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, Universal decided that if two monsters were good, three were better, and the “monster rally” was born. 1945’s House of Frankenstein brought together the monster (Glenn Strange), the wolf man (Chaney) and Dracula (John Carradine), with Boris Karloff playing the mad scientist for good measure.

In keeping with the bizarre requirement for musical entertainment, Elena Verdugo plays a gypsy girl who does a really hilarious dance number prior to becoming the apple of the wolf man’s eye. If contrived, the film was certainly brisk, clocking in at 71 minutes.

Even shorter was the same year’s House of Dracula, running 69 minutes. Strange, Chaney and Carradine were all back, none the worse for wear. And, of course, the hunchback nurse with the implant error that I referred to in Part One of this post, is in this one. Surprisingly, there was no musical number. A wasted opportunity — Strange could’ve sung “If I Only Had a Brain.”

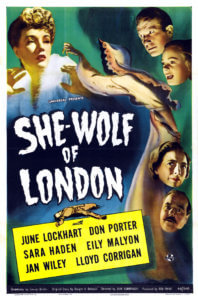

Sadly, these two films represented the final high water marks for Universal classic monsters. She-Wolf of London (1946), starring Lost in Space‘s June Lockhart, was a total cheat, a boring murder mystery with no wolves. And actor Rondo Hatton, who suffered from acromegaly, (a disease that enlarges facial features and limbs) starred in House of Horrors (also 1946), intended to be the first in a series of films about “the Creeper.”

Sadly, these two films represented the final high water marks for Universal classic monsters. She-Wolf of London (1946), starring Lost in Space‘s June Lockhart, was a total cheat, a boring murder mystery with no wolves. And actor Rondo Hatton, who suffered from acromegaly, (a disease that enlarges facial features and limbs) starred in House of Horrors (also 1946), intended to be the first in a series of films about “the Creeper.”

But the second Creeper film, The Brute Man, was sold to mega-low-budget Producers Releasing Company after the death of its star, with Universal worrying that it would just be too tasteless. And it was. When I saw the film being myst-ied by Mike and the Bots on Mystery Science Theater 3000, it certainly looked like it could have been made by PRC.

But the bottom of the barrel was yet to be scraped. The cheesy comedy team of Abbott and Costello was making tons of money for the studio, so they began to “meet” the creatures in 1948, including Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, the mummy, the invisible man and “the Killer” (Boris Karloff). A&C Meet Frankenstein is considered a classic of the genre, but those particular comedians are an acquired taste I’m afraid I was never able to acquire.

The 1950s brought with them the cold war, and the studio started turning to mutants and alien invasions. Some of these films are certainly classics, but they ain’t the classic monsters. It was left to England’s Hammer Films to resurrect the creatures in bloody full color. But that’s a story for another dark and stormy night.

The 1950s brought with them the cold war, and the studio started turning to mutants and alien invasions. Some of these films are certainly classics, but they ain’t the classic monsters. It was left to England’s Hammer Films to resurrect the creatures in bloody full color. But that’s a story for another dark and stormy night.