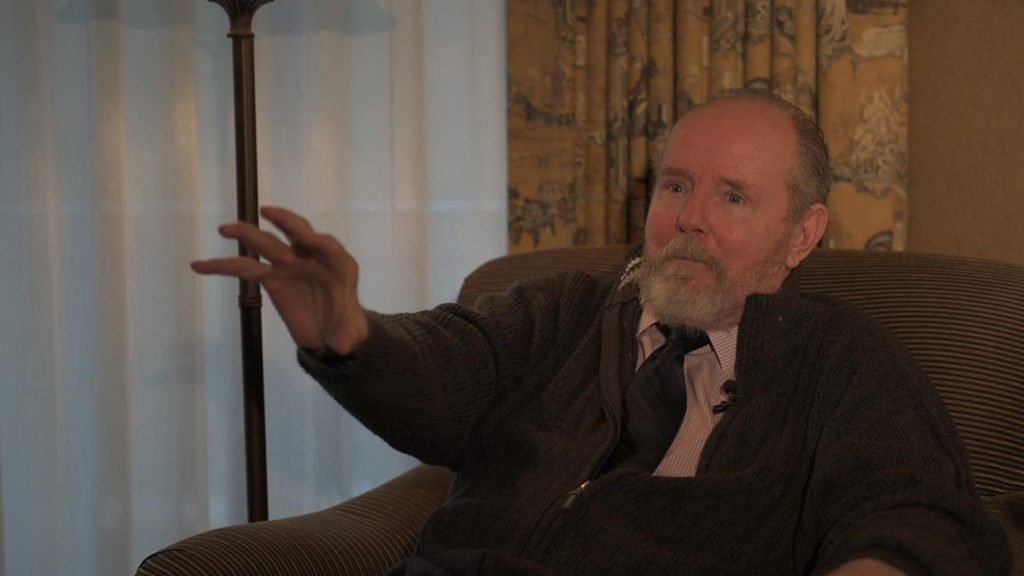

Exclusive Interview: Maverick Filmmaker Larry Cohen

Larry Cohen’s life has been truly amazing. A maverick filmmaker who broke all the rules but nevertheless managed to triumph in Hollywood, his career continues to this day. Now his work is getting its long-due recognition with Steve Mitchell’s documentary, King Cohen. The film tells the absorbing — and sometimes unbelievable — story of this indefatigable idea machine, who seems to have emerged from the womb already prepared to add his distinctive vision to the worlds of television and cinema.

Larry Cohen’s life has been truly amazing. A maverick filmmaker who broke all the rules but nevertheless managed to triumph in Hollywood, his career continues to this day. Now his work is getting its long-due recognition with Steve Mitchell’s documentary, King Cohen. The film tells the absorbing — and sometimes unbelievable — story of this indefatigable idea machine, who seems to have emerged from the womb already prepared to add his distinctive vision to the worlds of television and cinema.

In anticipation of King Cohen‘s release on Friday, July 20, Mr. Cohen granted me a phone interview from his home in Beverly Hills:

Can you remember the earliest inspirations that led you to become such a creative force in the industry?

I loved going to movies as a kid. It was one of my favorite things to do, and I always went several times a week. I usually sat through them twice. And I just always knew I wanted to be involved in making movies.

How did you first get into television?

By writing. I thought writing was the easiest way to gain entry into the business, because you could do it all by yourself and it didn’t cost you any money except to buy a ream of paper. So there was no overhead. I just inundated people with material until finally somebody bought something. I found out that I enjoyed writing, but I had been writing comic strips as a hobby when I was about eight or nine years old; drawing my own comic books with original stories. So I’ve been writing since I was a little kid.

That’s great! And you started creating television shows, too.

I wrote television series for a few years. I wrote for a show called The Defenders, which won the Emmy every year, and I created a few series: Branded, Coronet Blue, The Invaders. And then I decided I’d rather start writing my own movies. I wrote screenplays for other people at first, such as Return of the Magnificent Seven and Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting. I was doing very well, getting top dollar for my scripts, but I wasn’t happy with the way the movies looked. I always thought I could make a better movie from the scripts than the directors they put on them. And so I decided I was going to make my own pictures!

Just kept moving…

That’s always the key. Just keep moving ahead and keep coming up with something new.

How do you think today’s television compares with the 1950s and 1960s?

Well, today there are so many more shows on than there ever were before. You’re inundated with new shows. You don’t know what to look at first when you go to Netflix and you zoom by the list of all these projects. There’s just no way you can watch all these shows; it’s just impossible. Of course, series today are like eight episodes — that’s a series. When I started writing for television, we used to do 36 episodes a season. Can you believe that? 36 one-hour episodes, and all new.

In those days, the shows were longer because they only had six minutes of commercials. They’re weren’t allowed any more. Today, I think there’s about 15 minutes of commercials, so your show is only about 42 minutes long. And with seasons being eight or nine episodes long, you have to be on for five years to get as many episodes as we did in one season. It’s not the same business anymore.

When you see the shows today, you read all the credits — executive producer, associate producer, producer, producer, producer. There must be seven or eight producers on every show, and these people are already writers. They’re in what’s called the “writers’ room.” They write the show together in a group session. When I wrote, I’d write all by myself. I’d pitch an idea to the producer of a show, and they’d say, “Okay, go ahead. Write it.” I’d go off and write the script and deliver it, and they’d shoot it. That was it — a one-man operation. Today, there are eight people in the room writing the script together. I don’t know how they do it. I don’t want to know how they do it. To me, writing is a solitary thing.

What they do, though, is come up with some very good shows. I’m very impressed with some of the work that’s out there, but it’s not something I would want to do.

When you made films, you specialized in “guerrilla filmmaking.” With so many distribution platforms and ways of making films today, do you think that will make a comeback?

I don’t think it’s ever gone away. I think there are always people going out there and stealing some shots, but never to the extent that I did. And today, with all the security and terrorism threats, and the cameras located on all the street corners, you couldn’t get away with what I did. You wouldn’t even want to try. You can’t be running around with guns in the streets today.

That’s for sure! What would you say is the most challenging situation you faced?

It’s always the same thing — coming up with the money to make the picture. That was the worst part of making your own movies, which was finding someone to finance them. Once you got the money, though, making the movie was a pleasure, to me anyhow. I enjoyed it, I enjoyed my actors. I enjoyed the interplay and improvisation with them.

A lot of directors don’t like actors and are intimidated by them. They try to overcome it by being authoritarian, untouchable bosses who are above everybody. I never stooped to that. I always thought of it as a community effort. I was always improvising, coming up with stuff, giving the actors new things to do. I kept them active and involved, having a good time. They looked forward to coming to work every day, and they looked forward to working with me on another movie. I made kind of a party out of it for them.

Plus you were famous for providing work for actors who were considered by others to be “over the hill”…

Oh, I don’t know about that! They may have been older, but not over the hill. The actors I employed had been working steadily over the years. They may not have been playing the same kinds of parts they played when they were young, because they were now playing character parts — but they were still stars.

I wasn’t hiring anyone for charity reasons. I hired them because they were perfect for the parts. I loved working with them — Academy Award-winning actors I’d admired since I was a child. I tried to give them something exciting to do, the best part they’d had in the last couple of years. They all responded.

And you got the benefit of their experience.

Yeah! I worked with people who’d been around a long time who’d worked at all the major studios and with all the big directors, but they’d never worked with someone the way I did. I’d make up scenes on the same day we shot. They’d just jump right in and do it. It was something they’d never done before, but they found out they could do it and enjoy it. I got as much pleasure out of it as they did.

Speaking of actors, you last worked with Michael Moriarty on the Masters of Horror episode in 2006. Do you still keep in touch?

Sure! We just did a film festival up in Canada. We were onstage for two days, bantering back and forth and having a lot of fun with each other. It was great seeing him again and hearing how enthusiastic he was about the work we achieved. It’s always nice to hear an actor who’s had a lot of credits over the years say that the stuff he did for you was his very best work. I mean, Michael’s won the Emmy award three times and the Golden Globe twice. He won the Tony award on Broadway for Best Actor. He’s one of the most honored actors in the country. Yet he seems to think that the work he did with me was among his very best work. Well, I accept the compliment!

Well, if you look at the work he did in Q: The Winged Serpent, for example, he clearly relished that role.

Hey, if you look at the work he did on Law And Order when he was the original star of that series. He made that show when it first went on the air. He decided to leave, but he could have stayed for years more if he wanted to.

What’s your secret to being able to adapt to the changing times, creating work that’s relevant in the 1970s but also in the 2000s?

I don’t think about anything external. I just write my own stuff. Right now, I’ve got ten one-hour episodes of a new series called High Concept, which is an anthology series of my work that I’m trying to package and get on cable. It’s one of my best scripts and very inventive. It’s called High Concept because every episode has a story that’s memorable in its way, and it’s something that people will talk about. With all the television and cable that’s on, you tend to forget everything you see, but these shows are all going to be classics. And it’s nice to still be in the game!

That’s awesome. What are your words of advice for up-and-coming filmmakers looking for their first break?

Write. Writing is still your best way to get in — if you have the talent. If you don’t have the talent, there’s nothing you can do about it. You have to find somebody to write it for you and then you put the package together. Believe me, though, if you can write, it’s a big addition to your talent portfolio. It’s something nobody can take away from you.

But there are too many people who can’t write. I’ve encountered them over the years. You meet producers and people like that, and they say to you in a meeting, “Well, I’m not a writer, but…”, and then they proceed to tell you how to write your script. That’s the kind of pomposity and nonsense you have to put up with, which I wanted to avoid, so that’s why I made my own pictures. I didn’t have to deal with all these people. 90 percent of the trouble in making films is the people you have to deal with.

On motion pictures of many sizes and shapes, there are five producers and sometimes more. You’re dealing with studio executives and distribution people. Before you know it, you’ve got people coming out of your ears! They want to give you advice that you don’t want to hear. I didn’t want to make all those movies. I got to do 20 that I could write, produce and direct without interference. And I had a number of films I had to abandon — projects that I started and walked off of or projects that I cancelled after one or two days. I’d probably have had five more pictures had I not decided that this wasn’t a journey I wanted to take. Once I found out there was interference, I would go my own way.

I know you were less than enthusiastic about the 2008 It’s Alive remake…

Oh, it was a disaster.

Are there any others that you’d like to see rebooted?

Not particularly. People call up all the time about wanting to do The Stuff or God Told Me To, or whatever, and I say, “Come back with a financial offer that makes sense and we’ll talk about it.” I’m willing to listen to anybody, but the remake of It’s Alive in Bulgaria was just amateur night. The picture was hardly released at all, and that’s the best thing. It’s not worth seeing; it’s just a miserable mess.

The producer of it, Avi Lerner, apologized to me one afternoon in passing on the streets of Beverly Hills. He said, “I want to apologize to you for the terrible job we did with your property.” I said, “That’s fine. The check cleared,” and that was all I could tell him! They did pay me a considerable amount of money for it, so it wasn’t a total disaster from my point of view. And I was happy that my original was still the best one.

I remember seeing your original for the first time at a small theater in Michigan and being very captivated by it.

It still plays all the time. They just put out a box set of the It’s Alive Series on Blu-Ray. Also my comedy, Full Moon High, and The Ambulance, a thriller that I’m quite proud of, with James Earl Jones, Eric Roberts and Red Buttons. It’s one of my favorites. They’re constantly reissuing my movies in different forms and it’s nice, since some of them are 40 years old. How many movies are 40 years old and still actively playing?

And being exposed to new audiences.

Yeah, right. And after this documentary comes out, they’ll be more interested in my films.

What of all your achievements in the industry are you most proud of?

I’m proud of the whole package of movies that I made. I know that if I hadn’t made those movies and just written screenplays over the years, I would have had a disappointing career. I might have made a lot of money, but I wouldn’t have been satisfied with what I’d done with my work. The fact that I went out and made my own pictures and controlled every aspect of them — that’s very rewarding to me. Sure enough, people are starting to appreciate the number of the films we made, and the quality. I thought, “Some day, I’ll get discovered,” and apparently it’s happened.

I had nothing to do with the King Cohen movie. I had no input, but I’m reasonably pleased with the result.

I thought it was humorous how your recollections contradict Fred Williamson’s [star of Hell Up in Harlem and Black Caesar] in King Cohen.

Well, Fred wasn’t telling the truth, unfortunately! He didn’t want to admit that I had to do all his stunts for him first. It’s pretty clear if you look at the [documentary], there’s a still of Fred and me standing together, and I’m covered with coal dust from head to toe. That’s because I went into the coal pile before him in the action sequence where he gets buried in coal. He wouldn’t do it until I did it. Obviously, I went in ahead of him — there’s no reason I would have gone in after him.

But Fred’s a wonderful guy, and we have a great time. We’re always needling each other and having fun.

King Cohen begins its theatrical run July 20 in markets including Los Angeles and New York.

Special event screenings of the film will also be held throughout July and August in cities including Asheville, VA , Austin, TX, and Yonkers, NY.